More than anything else, when it opened in 1999, Bandon Dunes was a bold question: Would players make the trek to a true Scottish-style links in a remote part of southern Oregon—to walk a course designed by a then-unknown architect? The answer, of course, was a resounding yes. But during construction, the pressure to build a truly remarkable course was immense. And much of it hinged on the drama surrounding what would become its most famous hole: No. 16.

Exploration

“Watch your step!” yelled Shorty as he pointed to what I later discovered was a bear trap. It was July 1994 and my first day walking what is now Bandon Dunes. Shorty Dow, the on-site caretaker whom owner Mike Keiser had inherited when he purchased 1,600 acres of Oregon coastline, played guide to my father and me.

Born and raised in Scotland, I had never seen the Pacific Ocean before. I was 26, four years out of college, son of a prominent greenkeeper. My father, Jimmy Kidd, was still in charge of all the courses at the famed Gleneagles Hotel back home. We traipsed across the acreage from below what is now The Preserve to the back woods where the practice center now resides.

At that time the land was covered in gorse, but not gorse any Scottish golfer would know. This instead appeared to me an alien version reveling in the mild conditions and passive ecosystem of the Pacific Northwest. This version was taking over, choking out all competitors, racing across the land like an epidemic. Gorse was the greatest threat to the landscape, but Mike saw an opportunity. He had a plan that could beat the gorse back, reveal the sand dunes beneath and create something that just might bring players back to “golf as it was meant to be,” as I later wrote in the yardage guide for Bandon Dunes.

We walked to the coastline along a narrow four-wheeler trail between walls of 2-inch thorns and bright-yellow flowers that defend and beautify the demon gorse, and we could see nothing else. But we could hear the crashing surf, smell the sea air, feel the pounding waves. This sense of anticipation exists in us all as we near an ocean, and we were not not disappointed. As we broke out of the corridor of gorse near today’s 16th green, our senses were overwhelmed: More than 20 miles of coastline appeared 100 feet below. As far as the eye could see from Cape Blanco to Cape Arago, breakers formed a half mile out to sea and rolled to shore, building for their one moment of glory, crashing up on the North American continent, sliding up the sand in a froth before receding.

Agreement

If you had to cross the continent by pack wagon, this is the spot where you’d want that momentous journey to be rewarded. On every visit to Bandon, before, during and after construction, this point has been the destination for me, just like it has been for every visitor who makes the effort to travel there—the edge of a continent where one can survey the largest ocean on Earth.

The layout of Bandon Dunes was always about this very point on the land. In the early planning stages it was considered for the clubhouse, but a green simply had to be there. It had to give the golfer a moment to pause, take in the grandeur of it all and relinquish any thoughts that they are bigger or better than Mother Nature. This green had to be late in the round, but I still had to get golfers back to the inland clubhouse that had since been planned, so it was decided that it had to be No. 16 green.

The spot had to be a green, but to what? A par 3 was the most obvious—think Cypress Point’s 16th or No. 7 at Pebble Beach. I considered that option, but the hole had to be played from north to south, and at par-3 lengths it would be blind and uphill, a no-go.

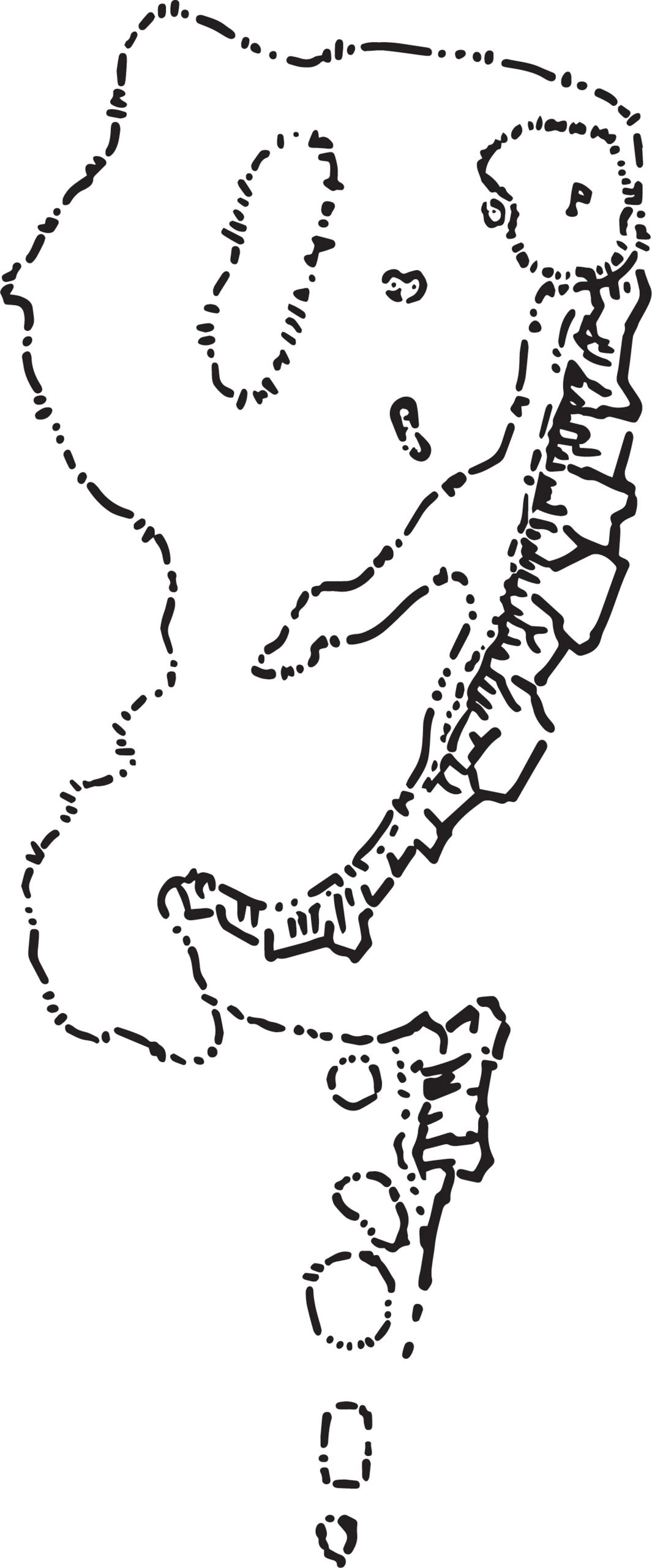

From my first visit in July 1994 through construction, which began in August 1997, this hole became pivotal to my relationship with Mike. We both knew how important this particular location would be to the identity of the entire resort. I had long talked about this hole with him, insisting on a large green set back from the cliff edge. Initially we discussed a long par 5, but when construction began we settled on a par 4. A natural ridge running north-south seemed to suggest a split fairway with two lines of attack. Mike liked the idea.

Inspiration

The 16th turned out to be the third hole we built at Bandon, after Nos. 12 and 15, both par 3s on the water. The tee location was set because No. 15 was already built, so we started there—“we” being the small crew assembled to create the course, led by me and Jim Haley, the lead shaper who had cut his teeth fresh out of the military with Pete Dye and later worked with Rees Jones. Jim had experience I didn’t have but shared my willingness to try anything. I still joke that, in the words of Forrest Gump, we were like “peas and carrots.”

When construction started, my creativity—and the pressure—kicked into high gear. Every idea that I had sketched was now under intense scrutiny. For me and many of my peers, golf-course design is not a desktop exercise. It’s a collaborative effort, an organic, expressive, sometimes chaotic mash-up of ideas from the team on the ground, orchestrated by whomever is in charge there. That’s why I always need to be on the ground. It makes me the conductor, the director and the lead creative. I get to take all the ideas, including my own, and be the final say on how a hole develops.

Jim shaped the tees from the open cab of his John Deere 450 bulldozer, the smallest of its kind used in golf-course construction. The smaller the blade on the bulldozer, the more skilled the operator, and Jim was Tiger Woods on that machine. He could make it do anything (well, anything but shape bunkers). I sat on the perfectly flat sand on the back tee as Jim moved forward to the next tee and mused the idea I had been selling Mike for four years. I started to play in the soft, wet sand all around me and shape the hole in miniature.

In this work, sometimes the original idea makes it to reality, but not often. The creative process wanders in one direction, then another, until eventually the best idea emerges (not without birthing pains). But occasionally an idea so pure, so clear, jumps into my mind as it did that day. I don’t know where it came from, I couldn’t remember seeing something like it and I’m not sure what inspired it. But there it was, clear as day in my imagination. And so it was at this moment. I scratched around on my hands and knees, shaping the idea in my head on the sand. My miniature golf-hole sculpture lined up with the land ahead of me, shaped in sand on the back tee of the very hole it was to become.

Bravery

I circled Jim’s dozer—approaching from behind can be fatal—and waved at him to track the machine off to the side of the hole. He was used to this; it meant I had an idea, and that meant changing the plan. Others would get frustrated, but Jim always took it in stride. He knew it was an essential part of our process. It was late in the afternoon, work was wrapping up everywhere else on the golf course and folks were headed home to family. Sunset was an hour away and a light rain fell as Jim brought the 14-ton machine to a halt.

He took one look at my artwork in the sand and got it, no explanation necessary. I had moved the green to the very edge of the continental United States. “Why wouldn’t you?” Jim would always say, and this was a perfect time to say it. Doing this made the hole more interesting, but not that much more strategic. The killer move was taking the very small ridge that initially split the fairway in two and emboldening it, steepening it, exposing the sand and making it, as I like to say, “speak” to the golfer on the tee. We had gone from two fairways to two options: the safe and the brave. Could a player take the bold line, trust their swing after 15 holes and clear this ridge into a tight fairway with the wind blowing? That would be the challenge for every golfer at No. 16 tee.

I literally ran down the unshaped fairway and planted two lines of red pin flags marking the top and bottom of the ridge, emanating from the seaward side of the hole and where an existing ridge protruded into play, extending diagonally back toward the tee. Next I sprinted up to the proposed bunkers and marked roughly their location and size, and finally the green: a ring of green pin flags sitting mere feet from a 100-foot near-vertical drop to the beach below.

One nagging thought: This was not at all what I had sold to Mike. But the idea was pure; it was solid. I was also 28 years old, and who isn’t bulletproof at that age?

Jim fired up his steed and started to push. Next thing I knew it was like the final scene from The Legend of Bagger Vance, where Will Smith and Matt Damon played against Walter Hagen and Bobby Jones. I angled Jim’s and my truck toward the hole and set the headlamps to high beam. We were on a roll and we weren’t going to let nightfall interrupt our flow! Late that night, we slid into our chairs at Lord Bennett’s in town and ordered a bottle of wine and steaks. Tomorrow we’d put the finishing touches on what we hoped might be the hole of our careers.

Trepidation

A few days later, the hole was complete. Classic Scottish kidney-bean pot bunkers had been shaped by Roger Sheffield, a local logger, in his excavator. Jim floated the hole off with a box blade behind an old tractor borrowed from a local dairy farmer. Drainage and irrigation lines were staked, but no trenches were dug. Mike was as clear then as he is today: Nothing gets put in the ground until he approves the hole. We had some time until his next visit, so the shaping crew moved to the 17th and we started the creative process once again. I tried not to think about the fact that I was blindsiding the biggest client—the only client—of my young career.

He arrived a few days later. I knew which day he was coming, but not the details of exactly when, or with whom, or how long he would stay; it didn’t work like that. I was out on the 17th working with Jim, Roger and the crew when we spotted Mike and a guest sauntering out across the open sand dunes toward No. 16. I knew the moment of truth was at hand.

Mike expected the hole I had been promoting, not the hole I built. When asked why Mike hired me—an unknown, untested young Scot—his reply back then (and ever since) was that if I failed him he would dispense with my services and change horses mid-stream. Those who know Mike know that he is a passionate golfer but an impassionate businessman. This was no idle threat.

I didn’t want to crowd him and thought it best for the new hole to speak for itself. I envisaged him cresting the rise behind 15, taking in the awesome new hole, marching down the fairway toward me and shaking me warmly by the hand, maybe even a pat on the back. I could see Mike and his mysterious guest were headed to the 16th tee. I headed back up No. 17 to 16 green to hopefully play out my dream scenario. Mike stood on the tee with his guest and from the green I could see arms waving and fingers pointing. I had no idea what they were saying. When would they start up the hole toward me?

Sixteen

All of a sudden, they both spun on their heels and walked back over the ridge and out of sight. The ground fell out from under me. He doesn’t like it; I didn’t consult with him first, he’s angry; I’ve embarrassed him in front of his guest; I’m screwed, home to Scotland, tail between legs. I decided to stay well out of Mike’s way for as long as possible to let the dust settle, thinking maybe I could talk my way out of this.

All afternoon, when Mike and his guest went in one direction, I would go in another. They walked the entire course, most of which was cleared at that point, and late in the day I saw them both return to No. 16. This was it. “It’s only sand; you can’t wear it out,” I thought. “If he doesn’t like it, I’ll reshape it back to the original idea.”

No harm, no foul, right?

Finally they stood on the revised 16th green near the cliff’s edge—the point where all of this began—and I briskly marched toward them, confident on the outside, petrified on the inside. Mike introduced his guest: It was my first meeting with Mike Davis, now chief executive officer of the USGA, one of the most powerful men in the game. Back then, he was still a rules official and tournament director.

Keiser drew on his cigarette (he smoked back then) and smiled. “Great hole,” he said. Davis agreed. The steak that night tasted just a little better, the wine a little sweeter. That moment gave me the confidence to never doubt my instincts again.